But nothing is guaranteed, and drought could force another mass liquidation of cattle.

Derrell Peel recently came to Pennsylvania with some welcome news: Cattle prices will be strong in 2022.

“It's nice to be here now and bring a little more optimistic view of things after everything we've been through the last couple of years," said Peel, a professor of agricultural economics at Oklahoma State University.

Solid demand and a tightening beef cattle market are the main factors Peel said will affect prices this year. The recent USDA beef numbers came out, and the report showed total cattle numbers at 91.9 million head, down 2% from last year, which is what he predicted at the Lancaster Cattle Feeders Day event in late January.

The U.S. beef cow herd peaked in 2019, he pointed out, but it’s been getting smaller the past couple of years.

“The cow herd is getting smaller. Sooner or later, that’s going to mean that feeder supplies get smaller,” he said. “The feedlot numbers are going to go down, and beef production is going to go down.”

Impacts from drought

About 70% of the country is in drought right now, including parts of Texas and Oklahoma where “extreme” drought is widespread, and even pockets of “exceptional” drought — the most severe drought status on the U.S. Drought Monitor website — are starting to pop up.

In Peel’s home state of Oklahoma, where winter wheat for grazing is typical at this time of year, the wheat is not growing. That means calves put out for grazing that normally come back in March are being brought back early.

Also, the dry conditions are ripe for wildfires and will be for the next couple of months.

BULLISH ON BEEF: Derrell Peel, ag economist with Oklahoma State University, told a group of Lancaster Cattle Feeders Day attendees that he expects cattle prices to be 8% to 12% higher on average this year, mainly because a shrinking beef herd and strong demand.

Drought is not a new story. The big difference right now is location. The most severe drought last year was in the Dakotas, eastern Montana and Nebraska, which led many producers to liquidate herds and caused marketwide impacts across the country, but nothing that was really severe.

Now, the drought has moved south. Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas, where more than a quarter of the country’s beef cattle herd resides, had relatively little drought last year, Peel said, but it’s getting serious now. A similar drought scenario was in 2011 when 1 million beef cows were liquidated in one year.

“So we’re vulnerable to another significant additional liquidation,” he said.

Places that had drought last year liquidated enough cows to get through this winter. Still, if drought conditions persist, there may be even more farms that will be forced to liquidate.

About 3.5 million beef cows were culled last year. Peel thinks the drought added upward of 350,000 cows to that total. “It will be bigger than that if the current drought conditions persist into April, May, June, July of this year,” he said.

Total cattle slaughter was up from 3.2% last year compared to 2020. Steer and heifer slaughter numbers were both up, and beef cow slaughter was up 9%, a clear sign of herd liquidation, Peel said.

The beef calf crop peaked in 2018, which he said should have led to peak feeder supplies in 2019, and then peak feedlot production in 2020. Feeder supplies did peak in 2019, but dropped a little into 2020. They did not drop in 2021, Peel said, for a number of reasons — including the fact that beef slaughter plants were not at capacity because of labor constraints and COVID-19 issues.

If you take out the month-to-month seasonality, the average feedlot inventory peaked last May and June. It would have peaked in 2020, Peel said, but because of disruptions and delays it was pushed into 2021. That is what created the big backlog the industry spent last year cleaning up.

With the cow herd peaking in 2019 and the calf crop peaking in 2018, Peel said that sooner or later, there will be a reduction in the number of cattle coming through the system.

A couple of things could disrupt that, especially if drought forces another large-scale liquidation. But that will leave a large hole at the other end.

“I think what we're going to see in 2022 is it becomes much more apparent industrywide that we don't have as many cattle,” Peel said.

“At the end of the day, as we work through 2022, I think cattle numbers are going to be significantly tighter, and I think it's going to become very apparent.”

Demand and exports

Corn prices are high right now, more than $6 a bushel. Feedlots will keep feeding cattle as long as they have them, Peel said. But when faced with significantly higher costs of gain, one of the ways they deal with it is placing them at larger weights, which can save feedlots several weeks of feeding.

Although last year’s corn crop was the second-highest on record, corn demand is still very high, driven largely from China.

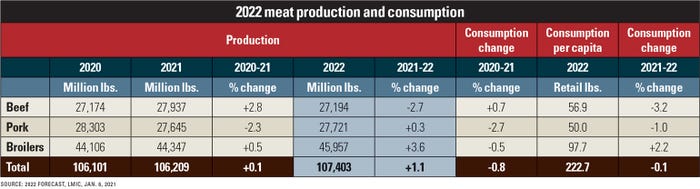

Total beef production last year was 27.9 billion pounds, up 2.8%, a record. For this year, Peel is projecting production to reach 27.19 billion pounds, down 2.7%.

"We've continued to take it higher. I think that stops this year because we're going to see decreased cattle numbers really take effect," he said.

Peel predicts per-capita beef consumption in the U.S. to be about 56.9 pounds this year, a 3.2% drop, but, "Don't read that as beef demand is falling. Per-capita consumption is just a measure of what we produce. If we produce less, we're going to eat less.”

On international trade, U.S. beef exports totaled 1.5 million metric tons last year, up 16% from 2020. Brazil is the largest exporter of beef in the world.

China is now the largest importer of beef and is the driver of beef prices globally, Peel said. While the Chinese don’t eat a lot of beef per capita, preferring other types of protein, even a small increase in a country of 1.4 billion people is significant, and he sees that demand going higher.

Beef exports might pull back a little bit this year, but not much, “as we continue to see growth opportunity in those export markets,” Peel said.

The U.S. also imports a lot of beef. In fact, the U.S. is the second-largest beef importer in the world. Between 60% and 70% goes to ground beef in the form of trim that’s added to fatty trimmings from fed cattle to “feed our enormous appetite for the Dollar Menu,” Peel said. But it’s an important market, he said, because it creates a market for trimmings that would otherwise be rendered and sold for much lower prices.

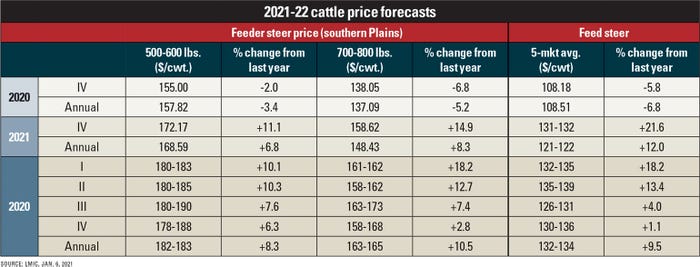

So what do drought, a shrinking cattle herd, and strong domestic and foreign demand mean for prices? Peel predicted cattle prices will be 8% to 12% higher this year, on average.

“The demand is good; the demand looks to stay good,” he said. “There are some potential things that could impact it, and obviously things can change. But strong demand combined with the fact that the supply side is getting tighter with declining beef production is a basis for strong prices.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like